Mass spectrometry is an advanced analytical technique used to measure the mass of molecules with very high precision. It is based on the generation of ions from chemical species, followed by their separation according to their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). Thanks to its exceptional sensitivity, speed, and versatility, mass spectrometry has become an indispensable tool in many scientific fields.

In a typical analysis, three main steps are involved:

-

Ionization — neutral molecules are converted into ions (e.g., ESI[1], MALDI[2]).

-

Analysis — the ions are separated according to their m/z by a mass analyzer (Quadrupole[3], TOF[4], Orbitrap[5], FT-ICR, etc.).

-

Detection — the ions are detected and a spectrum is generated, enabling their identification and quantification.

Advantages of mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry is distinguished by its very high sensitivity, allowing the detection of extremely small amounts of material, down to the femtomole level or even lower depending on the techniques used. It also offers excellent specificity, making it possible to differentiate compounds with very similar structures or masses. Through ion fragmentation methods (tandem mass spectrometry, MS/MS), mass spectrometry provides detailed structural information that is essential for the identification and elucidation of unknown compounds.

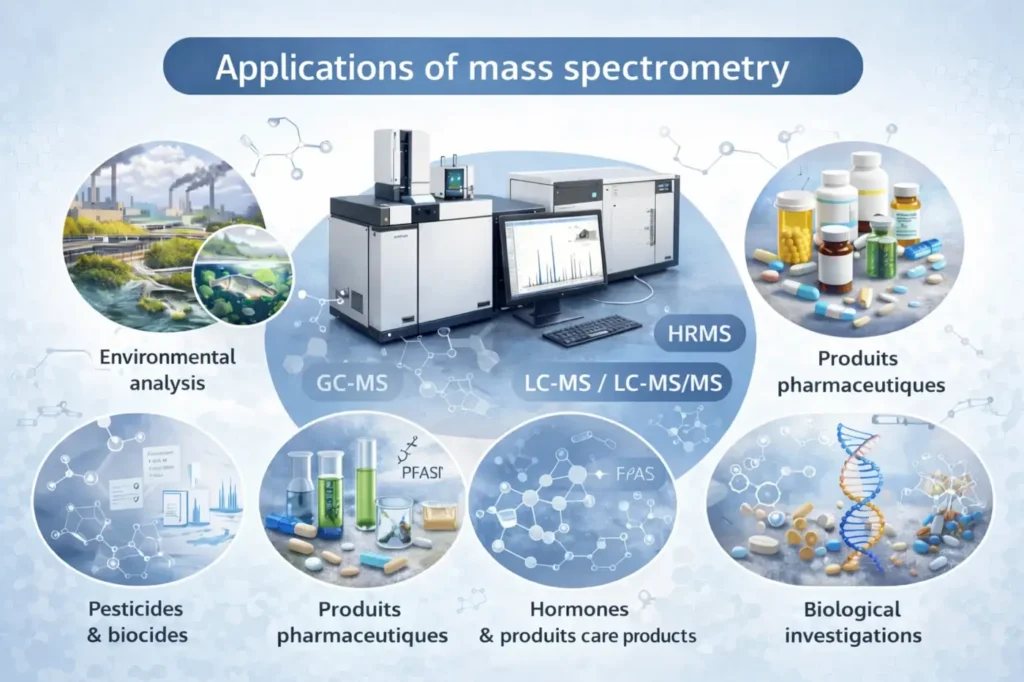

The wide range of available ionization sources enables the analysis of samples in different physical states (gas, liquid, or solid). This versatility allows direct coupling with separation techniques such as gas chromatography (GC-MS) or liquid chromatography (LC-MS), significantly improving analytical selectivity and sensitivity.

Moreover, the diversity of mass analyzers makes it possible to perform both qualitative and quantitative analyses with high acquisition speeds. This enables the simultaneous identification and quantification of a large number of molecules within complex samples, making mass spectrometry an essential tool in analytical chemistry, biology, environmental science, and pharmaceutical research.

Applications of mass spectrometry

Its applications cover a wide range of disciplines:

-

Chemistry: identification and characterization of molecules.

-

Biology and proteomics: analysis of peptides, proteins, and metabolites.

-

Pharmaceutical sciences: quality control, stability studies, and quantification of active pharmaceutical ingredients.

-

Environmental science: detection of trace-level contaminants.

-

Medicine: biomarkers, diagnostics, and targeted analyses.

Thanks to its ability to analyze molecules of all sizes—from small organic compounds to macromolecules reaching several hundred kilodaltons—mass spectrometry has established itself as one of the most powerful and versatile analytical tools available today.

Principle of operation

The three crucial steps of a mass spectrometry analysis

Step 1: Ionization

The molecules in the sample are converted into charged ions, a crucial step that enables their subsequent detection.

Step 2: Separation

The ions are sorted according to their mass-to-charge ratio, allowing each distinct component to be isolated.

Step 3: Detection

The separated ions are detected and recorded, making it possible to identify the exact composition of the sample.

Important criteria for a mass spectrometer

When comparing mass spectrometers, the most important criterion is sensitivity. This is followed by acquisition speed, a key parameter when quantifying molecules in combination with separation techniques such as chromatography. Indeed, it is necessary to acquire a sufficient number of mass spectra (scans) in order to properly reconstruct a chromatographic peak and accurately measure its area. Consequently, for the analysis of complex mixtures, a high acquisition speed is essential so that the mass spectrometer can analyze as many molecules as possible—particularly in MS/MS mode—with the aim of identifying the maximum number of compounds.

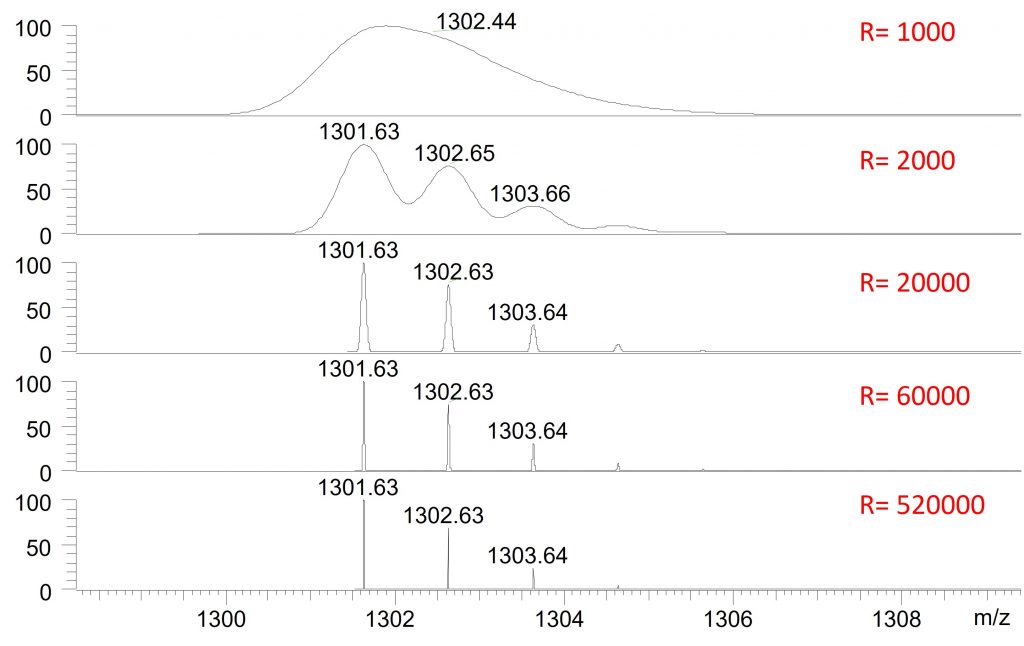

Resolution, which corresponds to the ability to distinguish two ions with closely spaced mass-to-charge ratios (m/z), is generally measured at the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the mass peak. This criterion is very often emphasized for high-resolution mass spectrometers. Although it is indeed important, it is less critical in the case of so-called low-resolution mass spectrometers, such as quadrupoles or ion traps, for which manufacturers sometimes do not even specify this value. For users who are not familiar with high-resolution mass spectrometry, it can be difficult to assess what constitutes a “good” resolution. The figure presented helps to illustrate this concept and provides a clearer visual understanding.

As shown in Figure 2, when the resolution is 1,000, the peaks overlap. This is a resolution typical of low-resolution mass spectrometers, such as quadrupoles or ion traps. When the resolution reaches 2,000, the different peaks begin to be distinguished. This level of resolution can be achieved with some low-resolution mass spectrometers operated in a so-called “high-resolution” mode, generally at the cost of reduced sensitivity and decreased acquisition speed.

At a resolution of 20,000—corresponding to the average resolution of a Time-of-Flight (TOF) analyzer or to an Orbitrap operated at low resolution—the peaks are clearly separated. At 60,000, which is the typical resolution of an Orbitrap analyzer, the peaks are even better defined. Finally, at a resolution of 520,000, representing the maximum resolution of an Orbitrap and a level that is readily achievable with an FT-ICR instrument, it becomes possible to distinguish ions whose m/z values differ by far less than one Dalton, as illustrated in the example.

However, the use of high resolution requires certain precautions. Although Orbitrap-type mass spectrometers generally do not require a significant sacrifice in sensitivity, they do lead to a slight reduction in acquisition speed. In addition, the resulting mass spectra generate very large raw data files, which can reach several gigabytes in size. In practice, for peptide or protein identification, resolutions between 30,000 and 60,000 are most commonly used, as biological samples are primarily composed of a limited number of elements (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, etc.), unlike environmental samples, in which nearly all elements of the periodic table may be present.

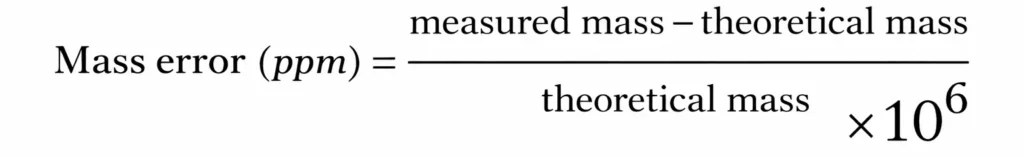

Mass accuracy is also a very important criterion. It makes it possible to confirm the identity of a compound or to obtain information about its elemental composition, particularly in the case of unknown compounds. Mass accuracy is expressed in parts per million (ppm) and is calculated as follows:  A mass error of 1 ppm, which corresponds to very good accuracy and is readily achievable with an Orbitrap or an FT-ICR instrument, means that for an ion with an m/z of 200, the error lies in the fourth decimal place. When identifying an unknown compound, good mass accuracy is therefore crucial. For example, for a compound measured at m/z 386.3544, a tolerance of 1 ppm leads to a single candidate that meets this criterion (C₂₇H₄₆O). In contrast, with a tolerance of 10 ppm, three different molecular formulas can satisfy the same criterion, making the identification more complex.

A mass error of 1 ppm, which corresponds to very good accuracy and is readily achievable with an Orbitrap or an FT-ICR instrument, means that for an ion with an m/z of 200, the error lies in the fourth decimal place. When identifying an unknown compound, good mass accuracy is therefore crucial. For example, for a compound measured at m/z 386.3544, a tolerance of 1 ppm leads to a single candidate that meets this criterion (C₂₇H₄₆O). In contrast, with a tolerance of 10 ppm, three different molecular formulas can satisfy the same criterion, making the identification more complex.

Brief history of mass spectrometry

1897 – The origins: J. J. Thomson

The history of mass spectrometry begins with J. J. Thomson, whose work on electrical discharges in gases led to the discovery of the electron in 1897. During the first decade of the 20th century, Thomson built the first mass spectrometer, then known as a parabola spectrograph. This instrument made it possible to determine the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ions. The ions, generated in discharge tubes, passed through electric and magnetic fields (single-focusing magnetic sector analyzer). Their trajectories were curved according to their m/z and detected on a fluorescent screen or photographic plate. Thomson was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1906 for his fundamental work on the electrical conductivity of gases.

1918 – Electron ionization source

The electron ionization (EI) source was invented by Arthur J. Dempster and later improved by Bleakney in 1928. It became the first ionization source to be widely used in mass spectrometry.

1930 – Double focusing

The double-focusing magnetic sector analyzer was developed. It corrects both spatial and energy dispersion of ions, leading to a significant improvement in mass spectral resolution.

1946 – Time-of-Flight (TOF) analyzer

The concept of Time-of-Flight (TOF) mass spectrometry was proposed by William E. Stephens. In a TOF mass spectrometer, ions are separated according to their flight velocities. This technique is fast, well suited for chromatographic coupling, and is now widely used in many analytical fields.

1950 – GC–MS coupling

Roland Gohlke and Fred McLafferty achieved the first coupling between gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (GC–TOF/MS), paving the way for structural analysis of complex organic compounds.

1955 – Quadrupole and ion traps

Wolfgang Paul introduced the quadrupole principle, in which ions can be selected, trapped, or ejected depending on the applied voltages. This discovery, recognized with a Nobel Prize, led to the development of quadrupole analyzers, triple quadrupoles, and ion traps, which are still widely used in modern mass spectrometry.

1966 – Chemical ionization (CI)

Chemical ionization (CI) was developed by Field. Being less energetic than electron impact ionization, it allows better preservation of pseudomolecular ions. Although the phenomenon had been observed as early as 1913 by Thomson, it was not correctly interpreted at that time.

1968 – Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS)

Keith R. Jennings and McLafferty introduced tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). Fragmentation of precursor ions is achieved through collisions with neutral gases, following the principle of collision-induced dissociation (CID).

1974 – FT-ICR-MS

Melvin B. Comisarow and Alan G. Marshall introduced Fourier transform techniques for processing signals generated in ion cyclotron resonance (ICR) mass spectrometers. This approach made it possible to achieve ultra-high resolution and exceptional mass accuracy.

1985 – MALDI

The MALDI (Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization) source was developed by Franz Hillenkamp and Michael Karas. This soft and highly sensitive ionization technique is particularly well suited for the analysis of biomolecules and biological macromolecules.

1988 – Electrospray ionization (ESI)

Electrospray ionization (ESI) was invented by John Fenn, who received the Nobel Prize for this major contribution. ESI enables efficient coupling of liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry (LC–MS). The production of multiply charged ions reduces the m/z range, making it possible to analyze very large molecules with excellent resolution.

2005 – Orbitrap

The commercialization of the first Orbitrap mass spectrometer (LTQ-Orbitrap XL) marked a true revolution. These instruments are distinguished by their high resolution, mass accuracy, sensitivity, rapid analysis, and robustness. Their ease of use also helps to reduce errors in spectral interpretation.

Référence

[1] Electrospray: Principles and Practice Simon J. Gaskell, https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199707)32:7<677::AID-JMS536>3.0.CO;2-G

[2] The Desorption Process in MALDI, Klaus Dreisewerd

Marie-Elisabeth Bougnoux a b, Cécile Angebault a b, Julie Leto b, Jean-Luc Beretti b